Douglas Scott Proudfoot is a former Canadian Ambassador who served as head of mission in Bamako, Juba and Ramallah. He was previously posted in Vienna (where he represented Canada at the IAEA, CTBTO and UNODC), London, Delhi and Nairobi. At headquarters he headed the Afghanistan and Sudan Task Forces. Most recently he headed the Canadian mission to the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). He is currently based in Ottawa. Areas of expertise include Africa; the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; fragile states & post-conflict situations; non-proliferation, arms control & disarmament; aviation; and, of course, Canada.

***************

The global aviation sector has an image problem. It is widely seen, not entirely without reason, as the bad boy in the fight to contain climate change. Putting people and goods into a large metal cylinder, and propelling it through the air at high speed, is inherently energy-intensive. Especially over short and medium distances, air travel is grossly inefficient, though before the pandemic we had got into the habit of frequent and frivolous air travel; after a temporary lull, it is again rapidly expanding. When climate equity is considered, air travel is deeply unequal: most of the planet’s population will never board a plane, but they suffer the consequences of aviation emissions.

On the other hand, aviation is an essential vector of development, needed for domestic and international communications, for high-value exports, and for mobility in education, trade, investment and tourism. Since air travel became commonplace it has immeasurably enriched our lives, and few among us would readily give up our overseas holidays or business trips. Although aviation accounts for only 3% of greenhouse gas emissions, this proportion is set to increase, and the sector must do its bit to address the threat that climate change poses.

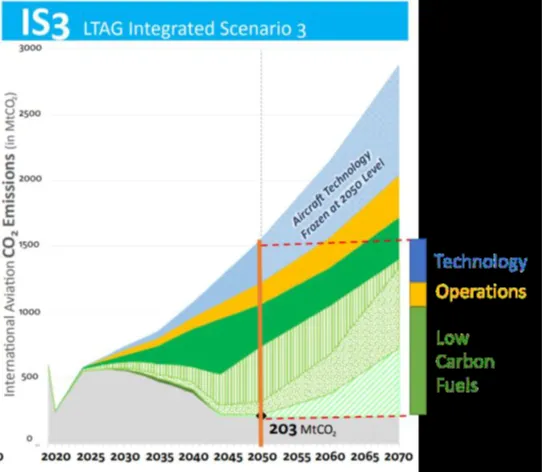

With that in mind, the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), the UN agency that governs aviation, reached a consensus last year on the need to bring the aviation sector’s emissions to net zero, and established the “Long-Term Aspirational Goal” of doing so by 2050. Wanly named, perhaps, but a meaningful target. The question is, how to attain it?

Planes are getting better…

Arguably, notable strides have already been made in the aviation sector. Engines have become 80% more efficient since the beginning of the jet age, but these gains in efficiency are more than offset by increases in volume. More recently, the new generation of aircraft, such as the Airbus A220 (formerly the Bombardier C-series) are 20-30% more energy-efficient than their immediate predecessors. Innovations in aerodynamics, engines, wing design, and lighter materials can further reduce emissions. Likewise, operational changes such as choosing better flight-paths or flying in chevron-formation (like ducks) can reduce drag and hence emissions.

A rule of thumb is that passenger and freight demand double every fifteen years. With that projected growth, the only way to achieve major emission reductions is by completely changing the energy source. Electric planes are already flying, but given their limited range will always remain a niche technology; hybrid-electric engines are under development, with the first flight tests planned for next year, and may also help a bit; and hydrogen power, which likely represents the future of aviation, is decades away from widespread adoption for aircraft. Carbon offsets, the subject of complicated rules developed by ICAO, are at best a stop-gap measure, as are the so-called “Low Carbon Aviation Fuels,” meaning fossil fuels whose supply chain reduces their overall carbon footprint.

…but only new fuels can decarbonise aviation

All this means that a transition to alternative aviation fuel is needed, and needed urgently. The bulk of emissions reductions in the next quarter century will need to come from “Sustainable Aviation Fuels” (SAF), meaning biofuel from waste or crops, and synthetic hydrocarbons using CO2 pulled from the atmosphere. SAF is now under production and in use, but remains more expensive than traditional fuel, by a factor of two to five times. What’s more, though planes are already using SAF mixed with regular fuel, often at 5% and sometimes up to 50%, there is a shortage in supply, and the necessary investment in refinery capacity will not happen without a greater degree of certainty about the future market. Estimated production of SAF will need to expand 1600-fold, necessitating the building or retooling of hundreds of refineries, and investments in the order of $3 trillions.

To provide greater predictability, and to de-risk investment in SAF, ICAO is planning a Conference on Aviation and Alternative Fuels (CAAF) in Dubai from 20 to 24 November, just a week before COP28 and in the same place. It is intended to provide the market signal needed to jump start a new SAF industry.

Aerospace manufacturers are leading the way, demonstrating that the demand for SAF will continue to grow. Their unpronounceable association, ICCAIA, recently announced the ambitious commitment of ensuring by 2030 that all new engines can take 100% SAF. But existing aircraft fleets, representing massive sunk costs, will continue to fly for decades. India alone ordered over a thousand new planes at this year’s Paris Air Show. So, manufacturers will retrofit engines to make them compatible with SAF, and work with fuel producers to devise “drop-in” fuel that will not damage the huge number of legacy engines which will remain in operation. This too presents an investment opportunity, providing there is a regulatory framework.

The debate in Dubai

The challenge of mobilising capital on the scale required for the transition to SAF is daunting. With economies of scale, and technical innovation, SAF costs will come down, just as they have for solar and wind power. But developing countries worry that they won’t be able to afford the new fuel, and will be shut out of its production. For that reason, Brazil is advocating that the CAAF create a new multilateral funding mechanism. There is little appetite among northern countries for such a new intergovernmental body, but even if the lion’s share of financing will inevitably come from private investment, there is a growing recognition that there must be a trade-off, and that blended finance, with a concessional element, will be needed if the global south can hope to keep up, and reap the benefits of aviation. And ICAO is already playing a role in helping developing countries adapt to SAF use; a compromise could be a facilitating role to encourage investment.

Another sticking point is feedstock. Theoretically, any organic matter, from sewage to maize to used oil from deep-fryers, can be turned into biofuel. But there are limitations imposed by cost, practicality and availability. After all, how many chips can we eat? There is an obvious need to avoid perverse and unintended consequences, such as diverting crops from food to fuel, or incentivising the felling of rainforests for palm plantations. A contentious issue to be resolved in Dubai will be Singapore’s call for “feed-stock neutrality:” it has the largest SAF refinery yet built, using mainly palm oil, which Europe excludes as an eligible fuel. A further complicating factor is that while all kerosene (the less glamourous name for jet fuel) is basically the same, biofuel varies in chemical composition depending on its feedstock, hence the need to fix norms, with the standards board ASTM given the role of assuring compatibility and safety.

Source: ICAO

But the biggest, and perhaps most contentious issue, will be targets. Aiming for net-zero aviation by 2050 is a fine goal, but to get there, greenhouse gas emissions will have to be cut by 5% per annum, while they are currently growing. There is, however, no consensus yet about what metrics to use for interim milestones: SAF uptake, emissions reductions, or something else altogether. The EU has mandated for itself a 2% increase is SAF use starting in 2025 and rising annually. The USA prefers to measure “carbon intensity” writ large. And others, such as China and Saudi Arabia, doubt the need for targets at all. The airlines cannot agree, and their association, IATA, has no position on the issue going into the Conference.

The CAAF may be overshadowed by the much larger COP28 soon after, and in any case a gathering of ministers and officials may sound like a mere talking shop, but if we are to travel in future without flygskam, and if we are to have a planet worth travelling around, what happens in Dubai later this month will matter to us all. And if it succeeds in establishing a global framework, SAF production will surge over the next five years and beyond, opening vast new opportunities.